After the group’s members published their first post (telling how each of us recalls first learning about a place called Greece, whether ancient or modern), our local coordinator, Vaia, sent us a message and proposed the topic of our second post. She wrote:

After the group’s members published their first post (telling how each of us recalls first learning about a place called Greece, whether ancient or modern), our local coordinator, Vaia, sent us a message and proposed the topic of our second post. She wrote:

“I was wondering what are you expecting to learn these three weeks, what do you think you’ll learn? … [O]f course visiting a new place is always exciting but what is exciting about visiting Greece?”

Good question. Whereas the first post was looking to the past, the second anticipates the future, though both are inevitably written from our positions in the present. Past perfect and future perfect, all rolled into the same moment–after all, even in grammar, whether you’re saying you had done something or that you will have done something, the saying of both is always, inevitably, in the present.

Although I’m returning to Greece for my fifth time, each time I go I find something new to hang onto once I’ve returned (like Sean’s wise “the same but different” response when asked about his breakfast on our first study abroad trip in 2008–we repeated that phrase so many times that year because it always summed up our experience of the strange familiar that we kept coming across); based on this I’m confident that, with new people traveling with me, new items on our agenda, and new places to visit, new memories will be produced. So just what do I think those memories will be….?

For starters, this will be the first time that I’ve stepped out of the airport in Athens. I’ve connected through Athens International Airport on a few occasions but have purposefully avoided visiting the city. Although many aspects of our study abroad course are an ongoing, collaborative work in progress–i.e., we’re a small enough group that we can easily adapt to changing circumstances and make parts of it up, as we go (e.g., Looks like a rainy day today? Ok, we’ll do the trip to Vergina tomorrow)–I’ve always seen at least one theme of our study abroad as working against stereotypes and as complicating commonsense. One way this is exemplified is in going to Greece and purposefully not going to Athens. That is to say, not serving up for our students the taken-for-granted knowledge that comes with them from their high school and university history courses, in which simple narratives of progress from past to present are often delivered. Going instead to Greece’s second largest city is one way that we do that–though we can’t help but be visitors, of course, we are immersed in a large, vibrant Greek city instead of in lines of tourists waiting to “walk in the footsteps” of the ancients. Sure, I fully realize that the narrative of ancient Greece that we carry with us is deeply woven (the first set of posts from our group makes that pretty obvious, including my own!), but going to Athens always struck me as catering to it just a little too much.

For starters, this will be the first time that I’ve stepped out of the airport in Athens. I’ve connected through Athens International Airport on a few occasions but have purposefully avoided visiting the city. Although many aspects of our study abroad course are an ongoing, collaborative work in progress–i.e., we’re a small enough group that we can easily adapt to changing circumstances and make parts of it up, as we go (e.g., Looks like a rainy day today? Ok, we’ll do the trip to Vergina tomorrow)–I’ve always seen at least one theme of our study abroad as working against stereotypes and as complicating commonsense. One way this is exemplified is in going to Greece and purposefully not going to Athens. That is to say, not serving up for our students the taken-for-granted knowledge that comes with them from their high school and university history courses, in which simple narratives of progress from past to present are often delivered. Going instead to Greece’s second largest city is one way that we do that–though we can’t help but be visitors, of course, we are immersed in a large, vibrant Greek city instead of in lines of tourists waiting to “walk in the footsteps” of the ancients. Sure, I fully realize that the narrative of ancient Greece that we carry with us is deeply woven (the first set of posts from our group makes that pretty obvious, including my own!), but going to Athens always struck me as catering to it just a little too much.

There’s a reason, of course, to go to see the monuments in Washington DC, when visiting the US, but there’s likely also good reasons to avoid memorials to the official, sanctioned past and, instead, go somewhere else. Somewhere else is no more authentic, of course, but it at least complicates the legitimacy of the orthodox in a way that we’d never see if all we did was visit monuments to a (supposedly) golden age.

But this time we are going to Athens. We’re staying for two nights on either end of the trip in one of the hotels at the base of the Acropolis, and then taking the train to and from Thessaloniki (you wouldn’t believe how much cheaper the airline tickets were if we just flew to Athens–it seems that, instead of the Fates, it is now the myth of the free market that dictates that we pay our respects to Athena, the city’s goddess). So I am looking forward to seeing for myself this city that, not so long ago, was just a small village and which captured the imagination of 18th and 19th century mythmakers in such places as London, Paris, Berlin, and Washington–those who worked to invent new things that we now call nation-states by linking them to “the glory that was Greece” (as Edgar Allen Poe famously phrased it, in his 1831 poem, “To Helen”).

So I’m very much looking forward to seeing the recently completed Acropolis Museum; with this in mind, I’ve been reading up on the Elgin Marbles–correction, the Parthenon Marbles (there’s much in a name, you know–like Father Maximos, a Greek Orthodox monk on Mount Athos, who was recently interviewed on the US news magazine show “60 Minutes” and who made sure that the reporter didn’t classify icons as mere art.) I’m keen to learn more about the role that these ancient artifacts now play in building not a temple, as they once might have, but, instead, building a social identity, whether it is for the modern British (as a reminder of their once glorious past) or the modern Greeks (as–you guessed it–

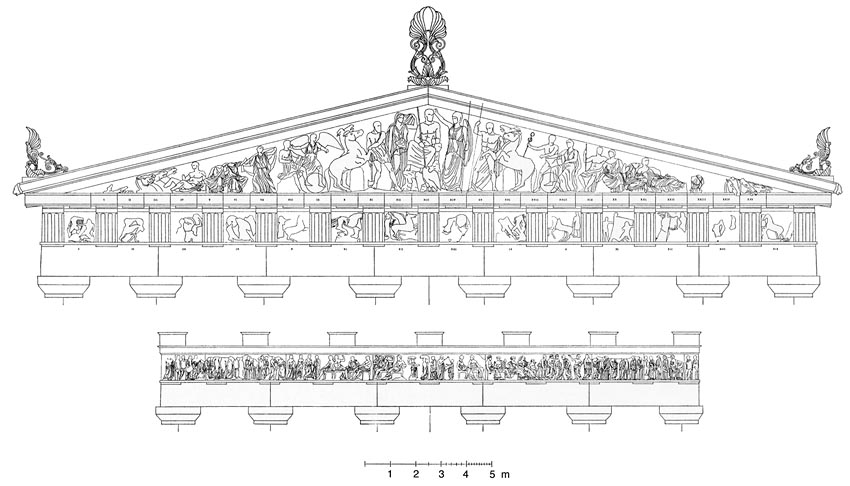

So I’m very much looking forward to seeing the recently completed Acropolis Museum; with this in mind, I’ve been reading up on the Elgin Marbles–correction, the Parthenon Marbles (there’s much in a name, you know–like Father Maximos, a Greek Orthodox monk on Mount Athos, who was recently interviewed on the US news magazine show “60 Minutes” and who made sure that the reporter didn’t classify icons as mere art.) I’m keen to learn more about the role that these ancient artifacts now play in building not a temple, as they once might have, but, instead, building a social identity, whether it is for the modern British (as a reminder of their once glorious past) or the modern Greeks (as–you guessed it– a reminder of their once glorious past). For in these marbles and monuments (which include fifteen of the Parthenon‘s 92 original metope [Greek μετόπη] panels, 17 sculptures from its pediments, and almost half of its original 160 meter long frieze–much of which is pictured at the top of this post) we find competing narratives, for whose glorious past do they signify? Are marbles, like the ancient Hebrew god apparently was, jealous in guardians of a sole significance? Instead, are they promiscuous, signifying virtually anything, to whomever? Or does all of this have nothing to do with the marbles themselves (for, like a text, they are mute on how they ought to be read) and everything to do with those who are doing the signifying and the competing meanings that they can attach to the cold stone that, since 1816, has sat in the British Museum.

a reminder of their once glorious past). For in these marbles and monuments (which include fifteen of the Parthenon‘s 92 original metope [Greek μετόπη] panels, 17 sculptures from its pediments, and almost half of its original 160 meter long frieze–much of which is pictured at the top of this post) we find competing narratives, for whose glorious past do they signify? Are marbles, like the ancient Hebrew god apparently was, jealous in guardians of a sole significance? Instead, are they promiscuous, signifying virtually anything, to whomever? Or does all of this have nothing to do with the marbles themselves (for, like a text, they are mute on how they ought to be read) and everything to do with those who are doing the signifying and the competing meanings that they can attach to the cold stone that, since 1816, has sat in the British Museum.

So, to answer Vaia’s question: I’m looking forward to a time when I will have remembered how the absent indicators of a glorious past are filled with meaning in the present, how missing monuments may someday return to a home that wasn’t there when they were taken.